Swoosh THIS

It was a simple idea. The day was hot and I needed a couple of t-shirts. Just something simple: Cotton. Maybe a bright color so my fitness class instructor can pick me out in the back row and correct my tricep-dip form. A wander through a Big Box store might be a way to cool off.

But shopping awakens the kraken of curmudgeonliness in me. So you seek a simple cotton t-shirt? Wouldn’t you prefer this deluxe poly-blend scientifically formulated to wick away moisture? (Cotton is so….Hanes-ish.) And what “statement” would you like your t-shirt to make? Shall it trumpet your love of The Rolling Stones? The Green Bay Packers? Heinz Ketchup? Do you prefer witty and retro? Ironic? Inspiring?

Prefer to keep your team allegiances and condiment choices to yourself? Well why not stand proud with team Nike? Declare yourself allied with Adidas? A lover of Lululemon? Want to tell passersby of your world travels? Your most recent concert experience? That you are a proud native of Buffalo, New York!

I understand the impulse. In college, I lived in a place called Zahm Hall and my dorm-mates were affectionately known as Zahmbies (Yeah, I was way ahead of the Walking Dead craze.) Eager to make a mark on Zahm’s social scene, I ordered a custom shirt—black with a shimmery skull in the center that declared my Zahmbie identity. I wore it to parties with orange Converse high-tops and stone-washed jeans (accented, at times, with a pair of rainbow suspenders—hey, it was the late 70s!).

I’ll not defend my fashion choices. But I guess you could say I was just developing my personal brand. Nothing unusual about that in these days of “influencers.” But I’m a bit wistful for a time when a “brand” was truly personal and creative. Not a hodgepodge of logos and marketing strategies.

Hate You Madly

Serendipity triumphs. A few lines into writing my anti-shopping screed, I happened on Mark Edmundson’s wise and timely editorial in the New York Times.

Emily Dickinson

Edmundson’s “I Hate, Therefore I Am” describes the landscape of multidirectional hatreds that zigzag through America and argues that snark is not necessarily the answer—whether directed toward Republicans, Democrats or wearers of t-shirts. Along the way, it offered a sweet reminder of a first encounter with one of my favorite poets.

My first serious writing teacher—way back in the late 1970s—was Professor James Robinson, a stately and kind soul who radiated generosity and good sense. Early in our college seminar, he told the dozen or so aspiring poets and novelists about the unusual necklace he wore every day: a leather thong holding a small flat stone, on which was printed “I’m Nobody.” He then recited the Emily Dickinson poem that inspired it:

I’m Nobody! Who are you?

Are you — Nobody — too?

Then there’s a pair of us!

Don't tell! they’d banish us — you know!

How dreary — to be — Somebody!

How public — like a Frog —

To tell your name — the livelong June —

To an admiring Bog!

I can still hear his voice in my head. For Robinson, Dickinson’s lines reflect her mythologized solitude, the Belle of Amherst retreating to her upper room to reflect and express the mysteries of the human condition. And the joys that might be found in that quiet space.

Edmundson’s article also quotes that Dickinson poem in full. But for him, being “nobody” means resisting the urge to define ourselves through our hatreds.

Libs hate conservatives, and conservatives hate ’em right back. People hate politicians, the elite, MAGA hats (and their wearers), social media (though they cannot stay away from it). Some hate the rich. Some despise immigrants. People hate the media. They hate corporations. They hate capitalism. They hate woke and cancel culture. They hate globalism and globalists. They hate this president.

He asks the trenchant question: “What if who and what we hate is who we are now?”

Edmundson argues that the “once-basic planks for building an identity [have] become useless for many”: our elevator-speech selves—formerly an amalgam of religious preferences, sports allegiances, home-town pride and leisure past times—have emptied out. To refill it, we need something else. Like hate, which he writes, “is the most reliable.”

Enter Dickinson. The possible solution, Edmundson argues, is the emptying of the self, to become a “Nobody” and embrace of “uncertainties, mysteries and doubts.” The handful of English majors among us will remember this as akin to John Keats’s “negative capability”—the simple attempt “to see the world from as many sides as you can.”

Perhaps it’s not so simple, but to avoid the vitriol that saturates the culture today, it’s certainly worth a try.

The Day the Music Died

Well, not all music. But the last few weeks marked the passing of musicians that meant a lot to me—at different times in different ways.

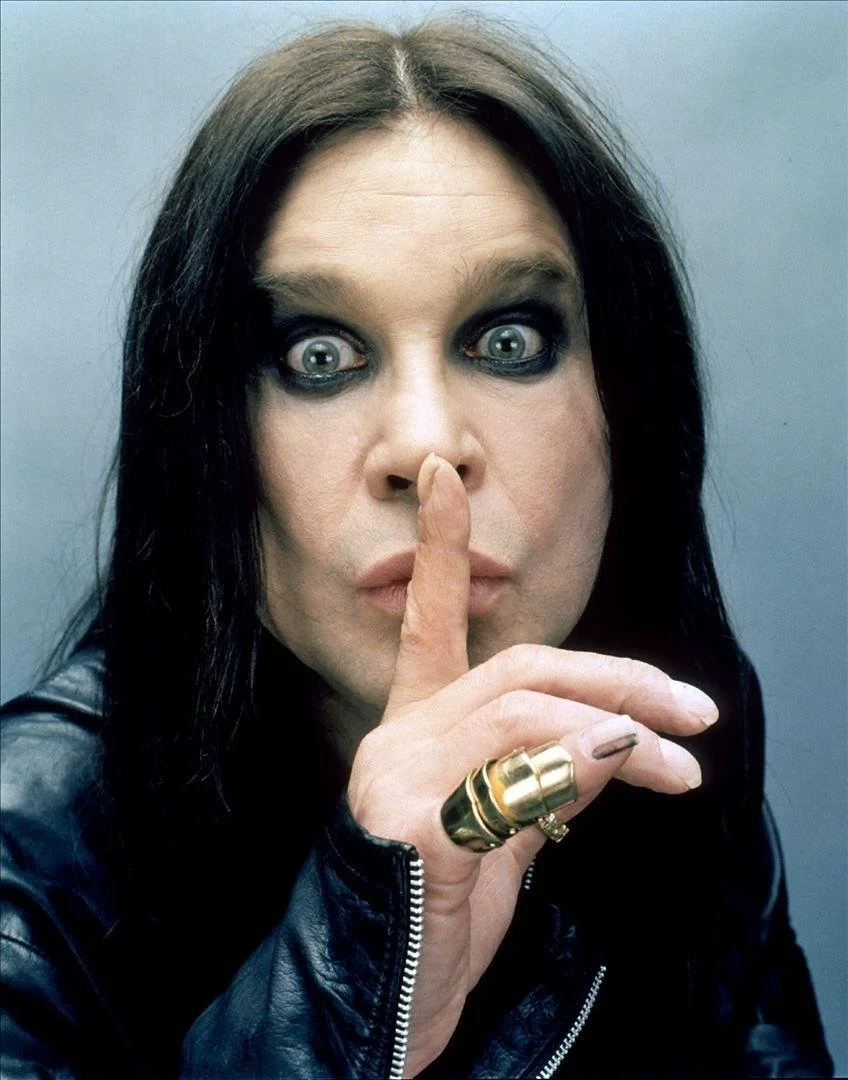

After I got my first stereo system—a combination AM/FM/Phono from that audiophile paradise, Sears, Roebuck and Co.—Black Sabbath’s Paranoid had pride of place on that phonograph spindle. I never borrowed my mom’s eyeliner nor chewed the head off a bat, but I heard “Iron Man” often enough to know the song by heart—both the screechy lyrics and the iconic guitar riff.

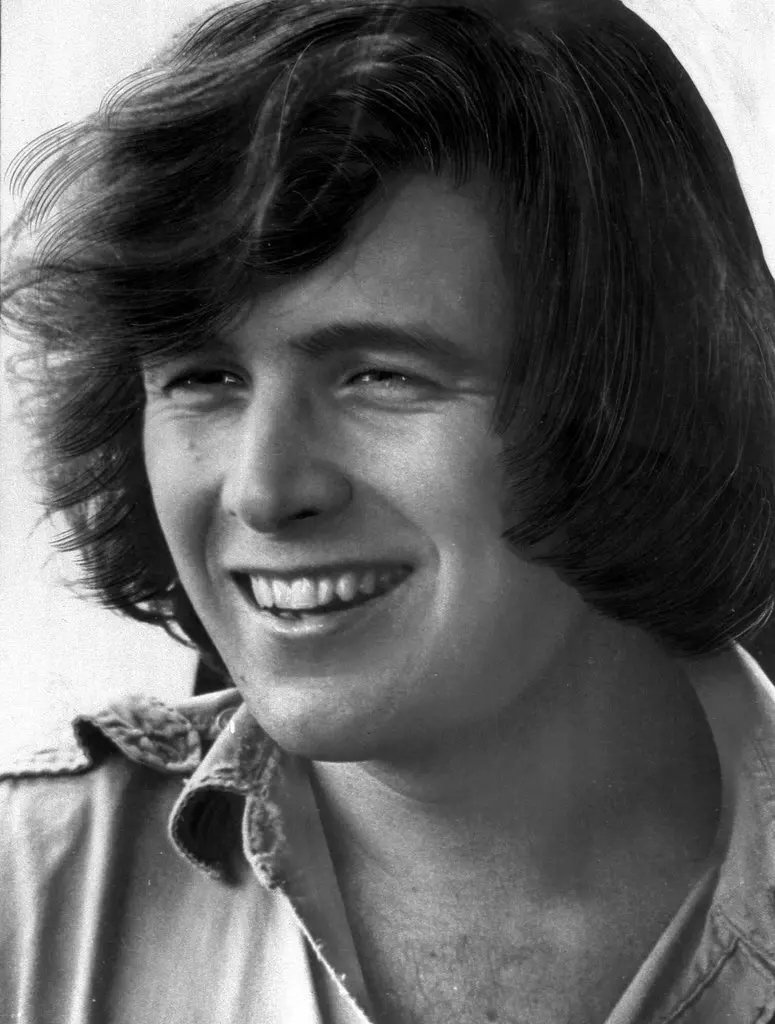

Mellowing into my tweens, I put aside my childish, headbanging ways and went acoustic, digging deep into the tender-hearted ballads of Don McLean. Sure, I could sing along to the eight-and-a-half minutes that came after, “A long, long time ago…” But my aspiringly sensitive soul also gravitated to songs like “Vincent,” “Castles in the Air,” and the lesser known, “And I Love You So.”

My lurch into the cynical teen years was helped by the discovery of Tom Lehrer, who was introduced to me by a nerdy New Yorker at a summer high school debate institute on the East Coast. One day between classes, he decided to serenade us with Lehrer’s “The Element Song,” a remarkable, high-speed patter that crammed the names of every element in Periodic Table into a familiar Gilbert and Sullivan melody.

In college, I mellowed. When friends visited my dorm room, I offered herbal tea instead of Old Milwaukee beer. I had a Magritte poster on the wall (you know the one) and jazz on the stereo. I wasn’t yet hip enough to imbibe in Miles Davis or John Coltrane, but offered guests the easy fusion sounds of Spyro Gyra and Grover Washington, Jr.. And, of course, Chuck Mangione. His silky flugelhorn lead on “Feels So Good” was definitely—and defiantly—a source of good feeling.

Lost & Found

Kathryn Schulz

Loss has been in my life and on my mind lately. And I’m grateful to Kathryn Schulz and her book, Lost & Found, for helping me navigate its waters. One of our most gifted essayists, Schulz’s book is a potent reflection on two major events of her life: the death of her father and meeting her future wife. Writing about her father’s death, she traces the idea of the mythical Valley of Lost Things from the Renaissance writer Ludovico Ariosto to Mary Poppins to L. Frank Baum’s Dot and Tot of Merryland.

Still, for all its charm, the Valley of Lost Things is, at its core. a melancholy place. The things we love are banished to it, and we ourselves are banished from it: the one feature every version of it has in common is that, under normal circumstances, it is inaccessible to humans. . . . As with the lost objects we love, so too with the lost people we love: we grant them an afterlife, in the bittersweet knowledge that, at least in this world, we will never again get to see them.

Rest in Peace

Charlotte Kosidowski, 1934-2025

Have a good week.